Biologist Juliet Daniel named one of Canada’s top Black innovators in research and medicine

Cancer biologist Juliet Daniel is being recognized by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) for her pioneering research on Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC).

“This article was first published on Brighter World. Read the original article.”

McMaster biologist Juliet Daniel is one of three Canadian scientists to be named a Black Innovator in Research and Medicine by the Government of Canada’s Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO). The award recognizes her pioneering research on Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), an aggressive type of breast cancer that disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic women.

The honour celebrates her groundbreaking discovery of the Kaiso gene, which some have called the “missing piece of the breast cancer puzzle”.

We sat down with Daniel to talk more about her research and her work as an advocate for Black voices in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Tell us about your discovery of the Kaiso gene

I was conducting postdoctoral research in Dr. Al Reynold’s lab at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., when I discovered the gene. At the time, I was trying to understand what caused tumour cells to break away from the primary tumour and metastasize (or spread) to other parts of the body or vital organs, such as the brain and lungs.

While conducting experiments to identify proteins involved in cell-cell adhesion, I identified a new gene, which I named Kaiso. Kaiso is the slang term for Calypso — a genre of Caribbean music that I listened to almost every night in the lab when I was cloning the gene.

How is the Kaiso gene connected to higher rates of TNBC in Black women?

Many scientists originally thought that the high incidence of TNBC in Black women was related to social determinants of health, like socio-economic status. While this theory may explain the poor survival rates, it didn’t really explain the root cause for the high incidence. That’s when I started looking for potential genetic links between TNBC and women of African ancestry.

During my research, I found that there were higher levels of the Kaiso protein in TNBC tissues of women from Nigeria and Barbados compared to white women. My research team is currently exploring ways to use Kaiso in cancer screening, and as a tool to aid in TNBC diagnosis and therapy.

Community outreach is a big part of your work. How have you shared your research to support education and awareness on TNBC?

About 10 years ago, I partnered with the Olive Branch of Hope — a community organization that supports Black women in the GTA living with cancer. Every year, we host breast cancer awareness and education workshops to help women of African ancestry learn more about TNBC. We host what I call “Cancer Biology 101” sessions that teach women the common terminology used by breast cancer researchers and oncologists, to help them better understand the disease and treatment process.

The workshops give women a safe space to talk about TNBC and discover ways to be proactive about their breast health.

You’re the co-founder of the Canadian Black Scientists Network (CBSN). Tell us about the inspiration behind this network and the work it does today

Early in my career, I noticed that there were few Black researchers at conferences I attended. For years, I was one of only two or three Black cancer biologists at the Canadian Cancer Research Conference. That lack of representation really perplexed me because my undergraduate courses had many Black students, yet students bemoaned the dearth of Black STEM professors! There seemed to be attrition along the pipeline to an academic research career.

My friends and STEM colleagues across Canada joked that we should start a Black scientists’ network. But we were all too busy being “the lonely only” at our academic institutions and we didn’t act on the idea — until the murder of George Floyd in 2020. That year, we created the CBSN. The network’s mission is to showcase and amplify the incredible work that Black scientists and professionals are doing across Canada — from trainees and graduate students to researchers and leaders in industry and government.

For Black youth especially, we hope the network shows that there are Black scientists paving the way for them and that they too can succeed in STEM.

CBSN recently started a Science Fair program to provide mentorship and financial support to Black high school students so they can compete in local, regional and national science fair competitions. Black youth are gifted and competent, but they often lack the support and opportunities to compete.

We were so proud when last year, three of our CBSN high school students won awards at Canada’s national Science Fair competition!

You’ve said that diverse perspectives in classrooms and labs lead to better, more innovative ideas. What role does diversity play in innovation?

After one of my first lectures at McMaster, three young female Black students came up to me after class and told me that they had never had a Black teacher before. That shocked me because the GTA is so diverse. For years, I was the only Black female professor in the Faculty of Science. I became a mentor to many Black students who were questioning their self-worth and wondering whether they belonged in STEM.

Diversity is so important in the classroom, in labs and in organizations in general. There has been research published over the past few years showing that companies with diverse teams achieve more economic growth than those without. And that makes sense: If everyone in an organization was raised in a similar environment and holds similar values, they will all tend to think alike. But when you bring individuals from different backgrounds together, they learn from each other and discover different ways of doing things.

Diversity stimulates creativity and makes us better innovators and problem-solvers.

What words of encouragement do you have for the next generation of Black scientists and innovators?

There are many of us working hard to ensure that future generations of Black scientists are not the only Black individuals at their organizations and schools. With the current resurgence in anti-Black racism, it can be very disheartening for many Black people, especially Black youth, to find spaces where they can succeed. My advice is to find yourself a great mentor and an advocate that will support and encourage you.

If you have a passion, a purpose and determination, you can achieve success — no matter how many obstacles you encounter. It may take longer than you planned, but it’s not a race. We’re trying to solve global problems, and that takes time, perseverance and a positive attitude.

My favorite mantra that I always say to my students is “It’s your attitude, not your aptitude, that will determine your altitude.”

Related News

News Listing

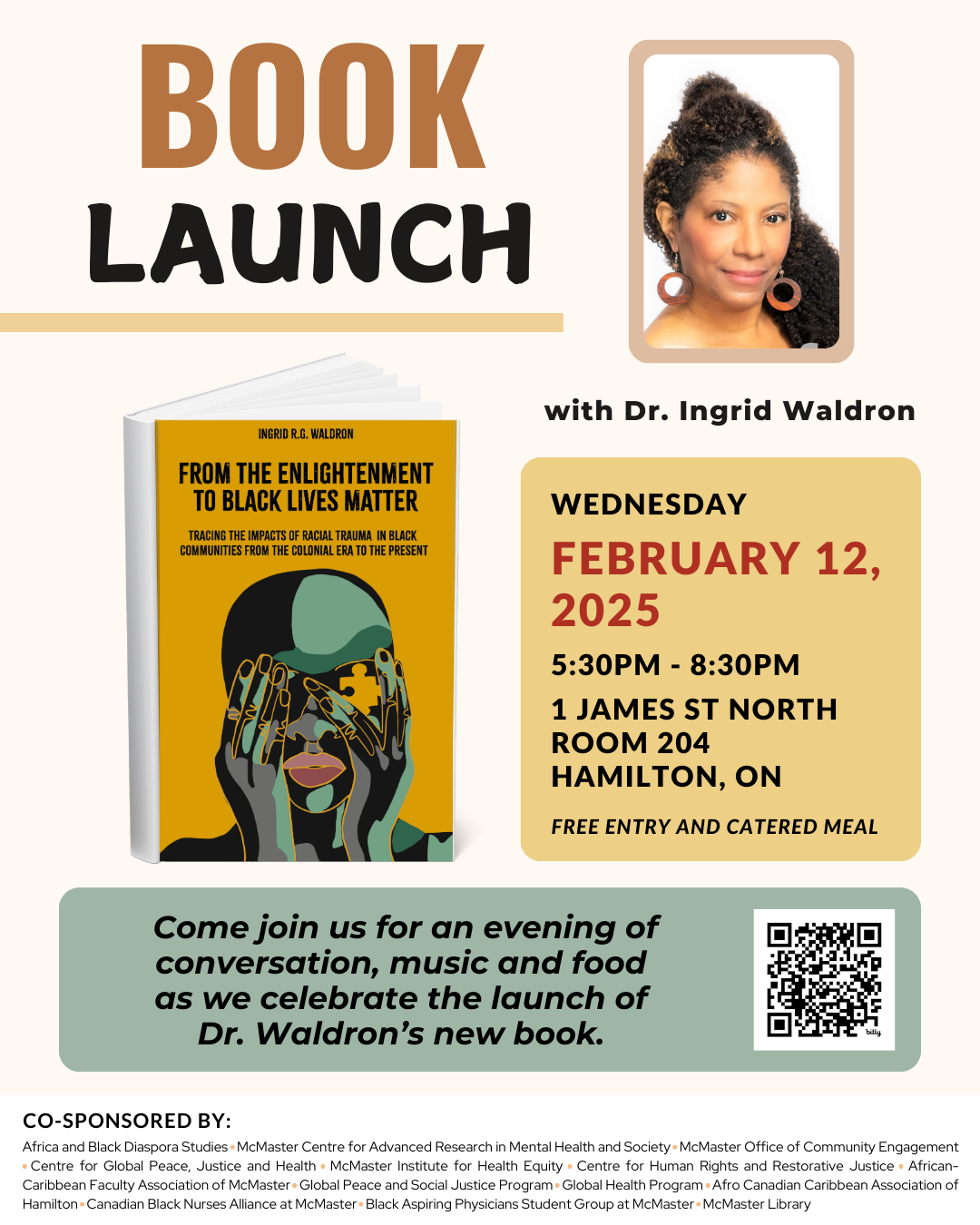

Bill developed and championed by HOPE Chair in Peace and Health Ingrid Waldron to become Canada’s first environmental justice law

Community, Research

July 30, 2024