Call for Chapter Proposals: Decolonizing Media and Communication Studies Education in Africa

We are seeking abstracts (250 words maximum) together with a short biography and subsequently 6,000-word chapters for an edited book that explores the topic of decolonizing media and communication education in Africa.

Deadline for submissions:

May 15, 2022

*Note: We are in communication with a publisher who has shown interest in this book. We have begun accepting and reviewing submissions. We already have chapters focusing on the following thematic areas: ‘Contextual perspectives: Decolonising education,’ ‘Rethinking classrooms: Implications for students, instructors, and instruction’ and ‘Reflections on the curriculum: Possibilities and impossibilities.’

Rationale:

March 2015 will forever be etched in the history of universities in South Africa as a turning point, moreso the University of Cape Town (UCT) as exasperated university students – later calling themselves the #RhodesMustFall (RMF) movement – called for the decolonisation of the institution. While the student protests were initially sparked and characterised by calls for the removal of the statue of infamous British imperialist, Cecil John Rhodes which was perched on the university’s middle campus, in their mission statement, the RMF activists contended that their struggle was against “the dehumanisation of black people at UCT” (UCT: Rhodes Must Fall Facebook page, 2015). One of their demands was a call for “implement[ing] a curriculum which critically centres Africa and the subaltern […]” (UCT: Rhodes Must Fall Facebook page, 2015).

While the #RhodesMustFall movement brings into sharp focus the “myth of a ‘postcolonial’ world” (Grosfoguel, 2007: 219) in contemporary South African higher education, the exposition of this fallacy is not new on the continent. Conversations about colonialism, coloniality and decoloniality foregrounded by UCT students have been happening for a long time in Africa (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2013, 2015; Achebe 1958; Ngugi 1986). Post the UCT Rhodes Must Fall ‘protest moment,’ the abovementioned discussions gained momentum in the academy. In media and communication studies, there is burgeoning scholarship whose overarching preoccupations are that of disentangling and liberating the discipline from existing asymmetries in global knowledge production (Mano and milton, 2021; Chiumbu and Iqani, 2020; Moyo, 2020; Mutsvairo, 2018) that have relegated to the margins “African modes of knowing, social meaning-making, imagining, seeing and knowledge production” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013: 8). The bulk of this scholarship prioritises decolonising research and theorising. Many researchers have tabled different propositions that celebrate pluriversal knowledges and participatory ways of producing knowledges. Scholars have grappled with the meanings of what Maori scholar and professor, Linda Tuhiwai Smith calls “researching back in the same tradition of ‘writing back’ or ‘talking back’, that characterises much of the post-colonial or anti-colonial literature” (1999: 7).

Although the above literature has provided important insights specific to research, discussions on decolonising media and communication studies curricula, teaching and learning in Africa have largely been sidelined. The few articles that examine this topic are mostly published in the mainstream media or tucked away in edited scholarly publications whose primary focus is not on curricula and pedagogy (Rodny-Gumede and Chasi, 2021; Karam, 2018). This neglect is unfortunate given that the curriculum and the classroom are central to the process of ideologically and intellectually shaping next generation media and communication scholars and practitioners on the continent. In that regard, it is imperative and urgent to critically examine who is teaching, what are they teaching and how they are teaching. Chapters in this book will critically examine and disrupt manifestations of coloniality in media and communication studies curricula, teaching and learning in sub-Saharan Africa from a decolonial perspective.

To appreciate the significance of this publication, it is important to locate it in the broader context of occurrences in the ‘postcolonial era’ in Africa. Many countries in Africa gained flag independence from different European colonial powers between the 1950s and the 1970s following protracted armed struggles waged by independence movements. Although colonial administrations departed and the “physical empire” was rammed back according to historian, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Omanga, 2020), this has not automatically meant the jettisoning and death of ideas and forms of power asymmetries between the colonisers and the colonised birthed in the colonial era. Grosfoguel (2007: 219) argues that former colonies remain ensnared in a “colonial power matrix.” Grosfoguel (2007: 219) uses the term ‘coloniality’ to describe the “continuity of colonial forms of domination […] produced by colonial cultures and structures in the modern/colonial capitalist/patriarchal world-system.” In making a distinction between ‘colonialism’ and ‘coloniality,’ Maldonad-Torres (2007: 243) explains:

Colonialism denotes a political and economic relation in which the sovereignty of a nation or a people rests on the power of another nation, which makes such nation an empire. Coloniality, instead, refers to long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labour, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations. Thus coloniality survives colonialism. It is maintained alive in books, in the criteria for academic performance, in cultural patterns, in common sense, in the self-image of people, in aspirations of self, and so many other aspects of our modern experience. In a way, as modern subjects we breathe coloniality all the time and everyday.

There are three analytical tools that have been proposed for understanding manifestations of coloniality: coloniality of power (Quijano, 2007), coloniality of knowledge (Quijano, 2007) and coloniality of being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007). Coloniality of power “articulates continuities of colonial mentalities, psychologies and worldviews into the so-called ‘postcolonial era’ and highlights the social hierarchical relationships of exploitation and domination between Westerners and Africans that has its roots in centuries of European colonial expansion […]” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013: 8). Coloniality of knowledge deals with how Western epistemologies cloaked as scientific, objective, universal and neutral meddled with and dislocated knowledges that existed in Africa. Coloniality of being addresses the deprivation of Africans of their full humanity by the colonisers, hence the need to decolonise the human (Steyn and Mpofu, 2021). Colonised Africans were lowered to the level of non-human beings resulting in their lives being marked by violence, sexual assault, maladies and death (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013). In light of coloniality, Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015) explains that decoloniality is emancipatory in nature. It is meant to release Africa and the world from coloniality, a spurning and discarding of colonial worldviews that persist and thrive today.

Given the reality of coloniality, contributions in this book that take up the challenge by Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2013: 7) who argues for the “[…] need for new intellectual and academic interventions that transcend the twentieth century mythology of a decolonized African world.” Articles included in this book will be organized into three main thematic areas: ‘Contextual perspectives: Decolonising education,’ ‘Rethinking classrooms: Implications for students, instructors, and instruction’ and ‘Reflections on the curriculum: Possibilities and impossibilities.’ Chapters addressing the themes and sub-themes listed below or on content that contributors may deem pertinent to the main theme of the book are welcome.

Topics (This list is not exhaustive):

- Disrupting coloniality in curricula, teaching and classrooms in Africa

- The history and decolonisation of media, communication and film studies curricula in Africa.

- Who needs to decolonise: Are all curricula the same?

- Historical transformations in teaching media, communication and film studies in Africa

- Media, communication and film studies and manifestations of coloniality in ‘postcolonial’ Africa

- How were/are lecturers constituted in colonial and contemporary media, communication and film studies education in Africa?

- Who should teach media, communication and film studies in Africa?

- Identities and positionalities in decolonising the curriculum

- Stakeholder perceptions on decolonising the curriculum

- Decolonising research methods and theory in media, communication and film studies

- Centering Africa, African knowledges, experiences and thinkers in the curriculum as part of decolonisation

- Canonical thinkers and canonical texts: What do we do with the White (mostly) male Western thinkers that have been the backbone of many modules?

- What do decolonised media, communication and film studies look like?

- How were/are students constituted in colonial and contemporary media, communication and film studies education in Africa?

- What knowledges, histories, and experiences do students bring to the classrooms?

- Decolonising the ways we see students (being sensitive to students’ struggles): Re-thinking of students as whole people who are sometimes contending with trauma that can be triggered by some course materials (the importance of providing trigger warnings for students for certain readings and videos screened in the course)

- Centering student engagement and decentering the idea of an all-powerful and all-knowing university/academics

- Engendering critical thinking skills: Equipping students to be African citizens

- Case studies of decolonised curricula and teaching practice in media, communication and film studies

- State, institutional, departmental autonomy: When does decolonizing the curriculum begin

- Covid-19, distance learning and decolonisation of the curriculum

Timelines:

Please email abstracts (250 words maximum) and short biography to decolonisingmedia@gmail.com by 15 May 2022.

The deadline for full chapters (6,000 words) is 1 October 2022. Please also use the above email address.

Chapters submitted for consideration should be original work and must not be under consideration by other publications. All articles will be subjected to a blind peer reviewing process. Final acceptance of chapters is subject to successful peer review.

Co-editors:

Dr. Selina Mudavanhu is Assistant professor in the Communication Studies and Media Arts department at McMaster University in Canada

Dr. Shepherd Mpofu is Associate professor of Media and Communication at the University of Limpopo in South Africa

Dr. Kezia Batisai is Associate professor in the Sociology department at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa

Related News

News Listing

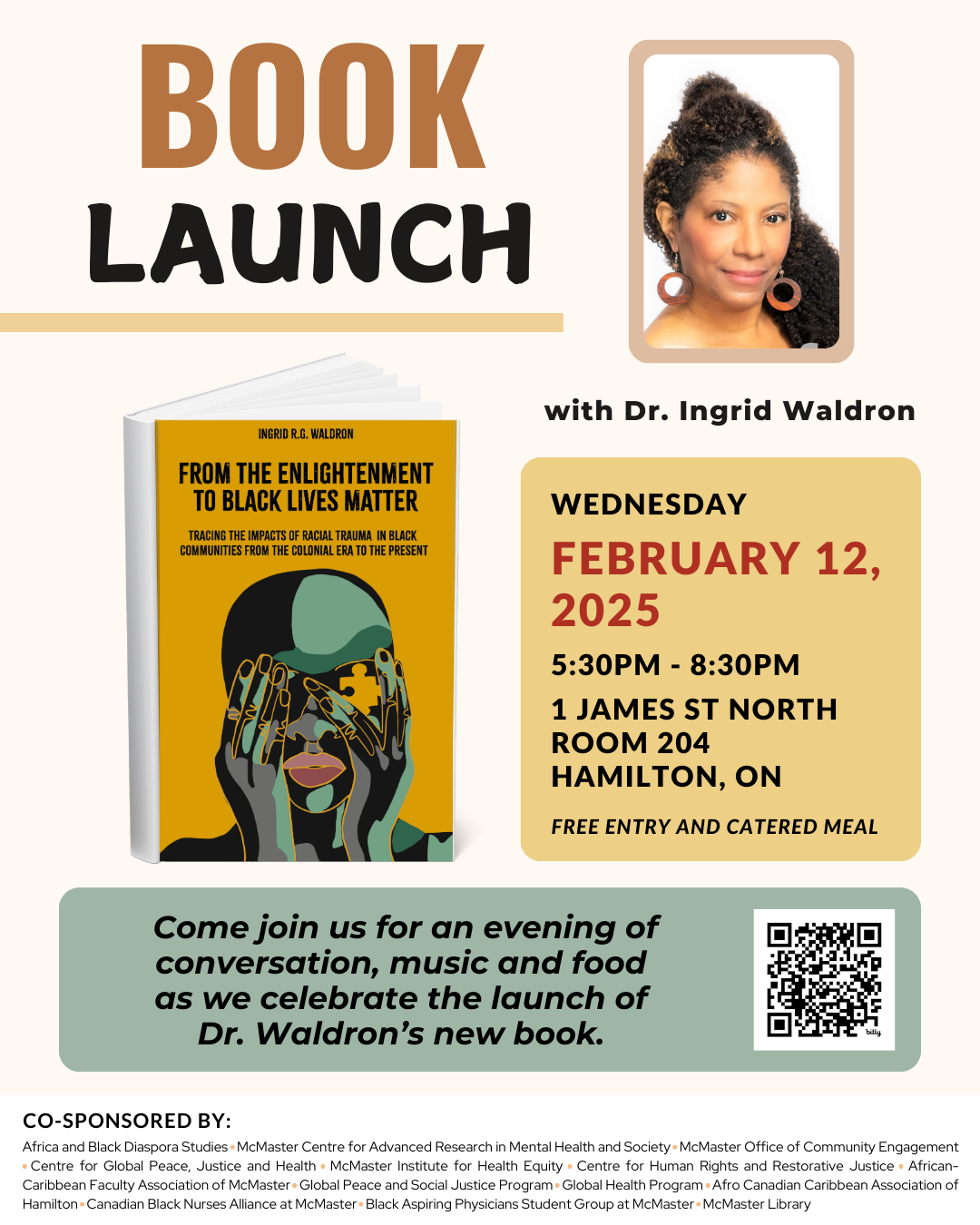

Bill developed and championed by HOPE Chair in Peace and Health Ingrid Waldron to become Canada’s first environmental justice law

Community, Research

July 30, 2024